Newsroom

Do you think only birds or mammals disperse seeds? Think again.

For a long time, scientists believed that when it came to seed dispersal, invertebrates – aside from ants – were mostly bystanders. Occasional sightings of wasps, beetles, wetas or slugs moving seeds were often brushed off as nature's oddities. But new research is challenging that assumption, pointing to a much bigger role for these overlooked creatures. Could invertebrates be the unsung heroes of plant life here on Earth?

Consisting of over 150,000 species, Diptera (flies) are one of the largest and most widespread insect groups we know of. Despite this, there were no proven cases of seed dispersal by flies – until now.

Researchers from the Kunming Institute of Botany (KIB), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), have confirmed that a type of fly, Bengalia varicolor, can act as an effective seed disperser in a unique way. They are kleptoparasites, meaning master thieves that steal food (and sometimes offspring) from ants. And here's the twist: give them their favorite food, and they'll starve to death rather than take a bite. But once an ant shows up with it? Game on!

Bengalia fly robbing a seed of Stemona mairei being transported by ant. (Image by KIB)

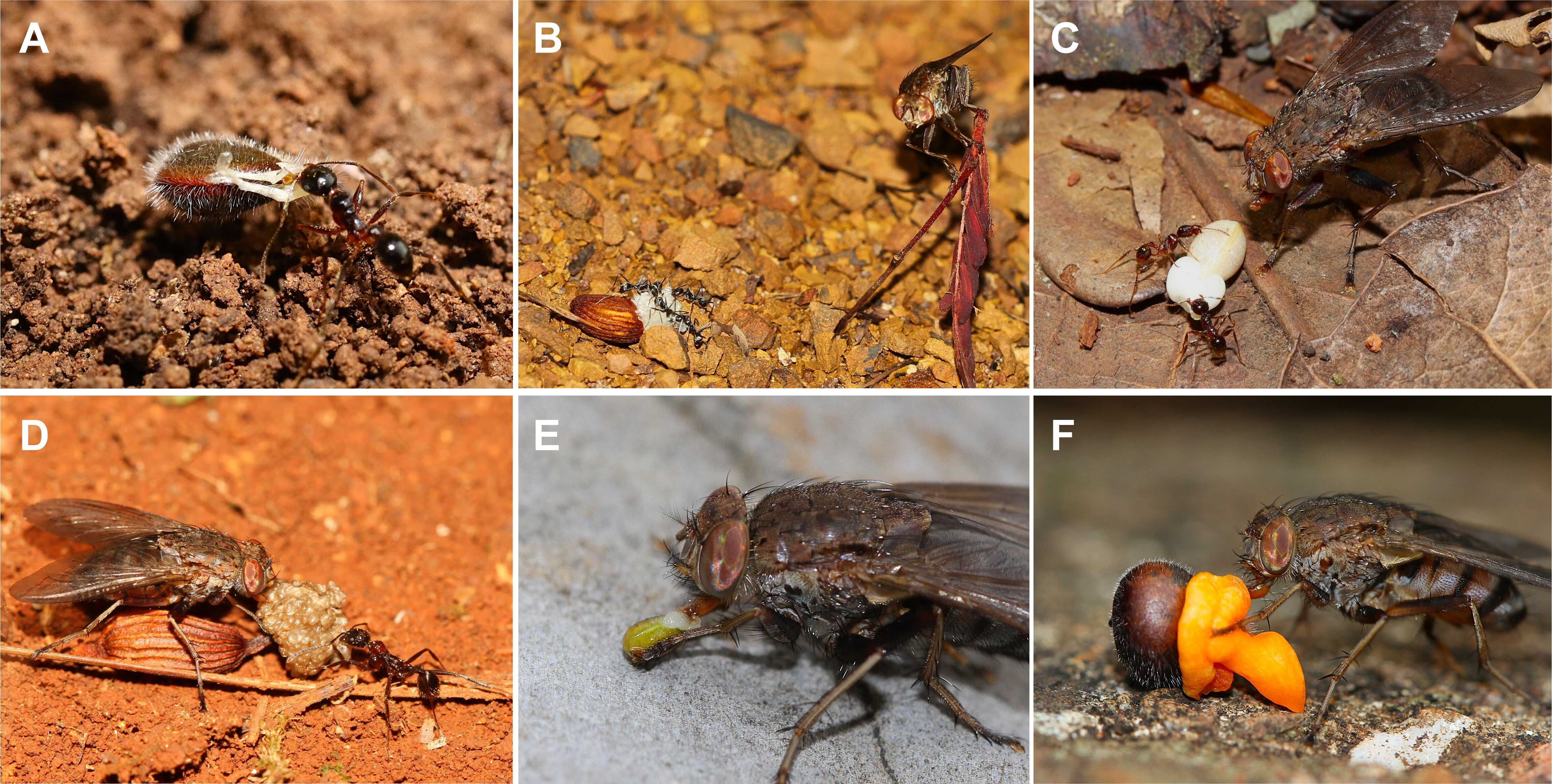

Spanning vast regions of Asia and tropical Africa, Bengalia flies share territory with plants that depend on ants to spread their seeds. That overlap raised an intriguing possibility: in these seed heists whereby flies swoop in to hijack ants, could the Bengalia flies be inserting themselves into the seed dispersal chain?

A research team led by Chen Gao at the KIB put the idea to the test.

Through long-term field observations and multi-year bioassays, Chen's research team delivered hard evidence that flies can act as effective seed dispersers.

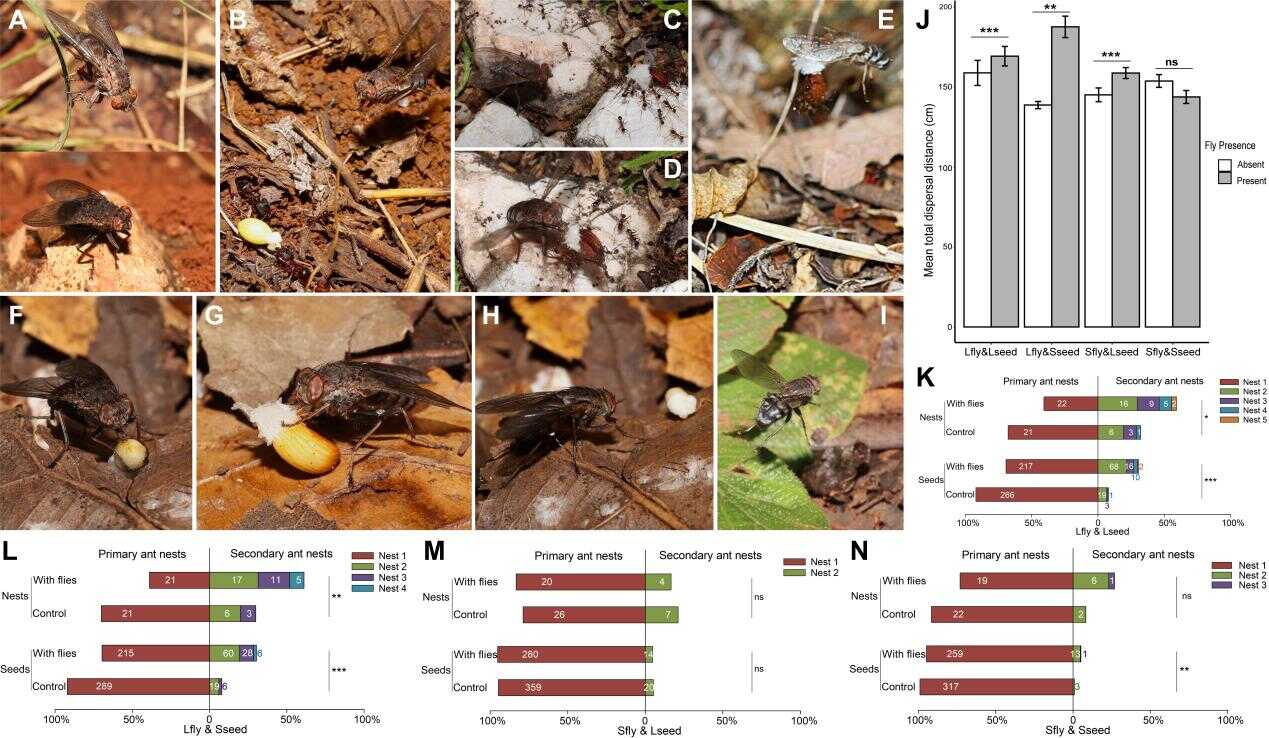

The breakthrough came when researchers offered seeds to ants in an area where Bengalia flies were known to live. As soon as the ants picked up the seeds, the flies swooped in to steal the cargo mid-transit. The process involves several key steps: drawn in by the sight of ants carrying seeds, the flies perch on nearby elevated points to observe. Then, in a swift ambush, they intercept the ants, clutch the seeds with their forelegs, and repeatedly take off to shake the ants loose. Once the seed is theirs, the flies feast on its fatty appendage, known as the elaiosome, before dropping the rest.

A Bengalia fly observing ants transporting a seed. (Image by KIB)

These discarded seeds are often picked up again by other ants, continuing their journey through the ecosystem. This unexpected relay – fly to seed to ant – reveals an intricate ecological interplay between animals and plants, and a complex and mutually beneficial relationship: the flies get a high-energy snack, and the plants get their seeds dispersed even farther than ants alone could ever manage.

To measure just how much these flies influence seed dispersal, Chen's team conducted over 170 experiments involving 2,580 seeds. They compared scenarios with and without Bengalia involvement and tested how seed and fly sizes affected dispersal.

The results were striking. Bengalia flies significantly extended how far seeds traveled, and often into more potentially favorable spots for germination. Even more surprising, the seeds weren't just moved once. A single seed could go through multiple rounds of hand-offs: carried by ants, stolen by flies, dropped, and picked up again by other ants. This "dispersal relay" could repeat up to seven times, creating a newly identified form of diplochory – a multi-stage seed dispersal system that dramatically expands a plant's reach.

Sequence of Bengalia flies robbing a seed from a transporting ant (A–I); comparisons of seed dispersal distance (J), number of ant nests reached (K), and seeds entering each nest (L–N), with and without Bengalia presence. (Image by KIB)

The research also revealed that Bengalia flies interact with a wide variety of ant-dispersed plants (involving plants from Stemonaceae, Celastraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Melanthiaceae, Papaveraceae, Polygalaceae), with its geographic distribution showing broad overlap with myrmecochorous plants. This suggests that fly-mediated seed dispersal may be a widespread and previously overlooked ecological strategy. More work across their range is necessary to confirm this. If true, it would mark a major shift in how scientists understand seed dispersal, adding flies to the list of active players alongside wind, water, mammals and birds.

Bengalia flies dispersing seeds of different plant groups: Polygalaceae (A&F), Stemonaceae (B&D), Celastraceae (C), and Papaveraceae (E). (Image by KIB)

The findings, titled "Seed Dispersal by Kleptoparasitic Flies," have been published in the journal Current Biology (Cell Press). (CGTN)