The Sichuan bush warbler was discovered after its insect-like song attracted the notice of researchers. 19 years on, it has finally been relocated and confirmed as a new species

"We heard a song that was unfamiliar to us coming from a dense patch of tall herbs close to the trail. The song didn’t sound very ‘bird-like’, and as we couldn’t see a trace of any bird, we were debating for a little while whether it was a bird or some insect”, recalls Professor Alström.

"Although we thought it was most likely a bird.”

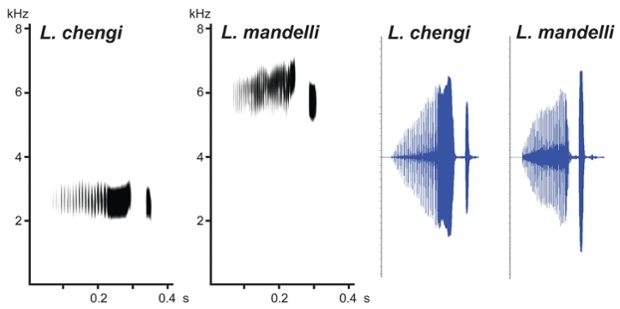

The sound they heard was a series of repeated phrases consisting of a drawn-out harsh note followed by a shorter note. This is the sound they heard on that particular morning in May 1992 (fig.2):

Russet bush warbler, Locustella mandelli, Laojun Shan, Sichuan, China, May 2014. (doi:10.1186/s40657-015-0016-z) Photograph: Per Alström

But this bird’s song was so strange! Was it

The two friends returned home to Sweden, pondering this mousy bird. Meanwhile, weeks lengthened into months and turned into years -- many years, in fact. During the ensuing decades, the two friends landed good jobs at separate universities in Sweden, relocated a few times and immersed themselves into their work, their colleagues and students, and their families. Yet neither forgot their encounter with that mysterious little chocolate-brown bird in the faraway mountains of China.

How did the research team realise this bird is a new species?

Nearly twenty years later, Professor Alström returned to China as a visiting professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. He was just as determined to find and identify this mystery bird as when he first heard it. Some of Professor Alström’s bird-watching colleagues in China had noticed this mystery bird, too. Soon, Professor Alström and his Chinese colleagues were even discussing this species using the provisional name they’d given it; “Sichuan bush warbler”.

The research team sets out into the forest in search of a new bird species. (Pictured: Min Zhao [right; student at Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing] and Professor Pamela Rasmussen [center; Michigan State University]. Hidden between is Professor Bo Dai [Leshan Normal University] and binoculars sticking out to the left belong to Jian Zhao [student at Sun Yat-sen University]). Laojun shan, Sichuan province, China, May 2014. Photograph: Per Alström

After learning that the “Sichuan bush warbler” and the russet bush warbler had both been found breeding in the Qinling mountains, a team was assembled to seek out both birds, to learn more about how they interacted with each other. Together with his Chinese colleagues Fumin Lei, Gang Song and Zuohua Yin from the Institute of Zoology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and Xuebin Gao from the Shaanxi Institute of Zoology in Xian, they mounted an expedition to the Qinling mountains, where they collected the first “Sichuan bush warbler” on 28 May 2011. This individual is the holotype for his species, which is to say that he is the one specimen that represents what the species looks like. This specimen is now housed in the Institute of Zoology at Chinese Academy of Sciences, along with sound recordings and a sample of his DNA.

Later, more individuals were spotted, captured and measured, their songs recorded and DNA samples collected.

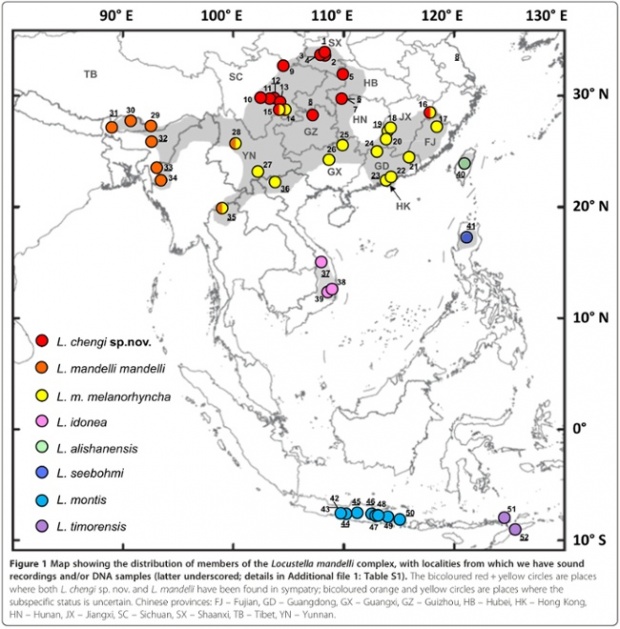

Back in the lab, mitochondrial DNA analyses of samples from birds in the genusLocustella revealed that these two bush warblers are very closely related. Further, these analyses estimated that the two species diverged from a common ancestor roughly 850,000 years ago (fig. 3).

The research team’s field studies found that the Sichuan bush warbler is locally common, and does not appear to be under any imminent threat.

By this time, the team gave this bird its formal names: its English name refers to Sichuan province where it was first discovered, and its specific name,

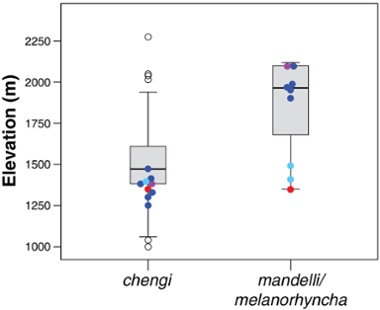

The Sichuan bush warbler is very similar to its closest relative, the russet bush warbler, but the two species are not identical. Which raises the question: short of carrying an automated PCR and DNA sequencer into the field -- laboratory equipment that can be as large and as heavy as a refrigerator-freezer -- how can an ornithologist or birder reliably distinguish these bird species, especially when they are hiding in an impenetrable bush, as they tend to do?

But the most obvious difference of all, especially for those who listen carefully to birds, is song. The Sichuan bush warbler sings a lower-pitched song with more drawn out notes (fig. 2) compared to the russet bush warbler (fig. 5):

Not only do these two species’ songs sound dramatically different, but a side-by-side comparison between the sonograms created from their song elements also look strikingly different (figure 6):

As an ornithologist and birder, a basic question that I’ve been pondering is which came first, the song or the species? Song is an important form of communication in birds. They use it to maintain their breeding territories, to advertise their overall fitness, and to attract mates. Since female songbirds choose their mates based on their songs, ornithologists are investigating how female choice influences the evolution of male song. These two, nearly identical, species that inhabit distinct niches and produce distinct songs could provide more insight into these two intersecting processes.

Another interesting question is the relationship between birdsong and habitat: did these two species’ songs evolve so they each travel most effectively through the particular niche that the singers live in? Research has shown that birds living in dense vegetation with a complex structure (a rainforest, basically) tend to sing songs with narrow bandwidths, low frequencies, drawn-out song elements and longer inter-element intervals, whereas birds that sing songs with broad bandwidths, high frequencies, short song elements and compressed inter-element intervals tend to live in more open habitats that lack obstructive vegetation (grasslands and the like).

But you don’t need to be a scientist or a birdwatcher to appreciate and be excited by the discovery of new species. Professor Alström pointed out in email: “ALL living organisms are interesting, and there are SO MANY cool creatures all over the world that are thoroughly enjoyable to observe.”

Sources:

Per Alström, Canwei Xia, Pamela C Rasmussen, Urban Olsson, Bo Dai, Jian Zhao, Paul J Leader, Geoff J Carey, Lu Dong, Tianlong Cai, Paul I Holt, Hung Le Manh, Gang Song, Yang Liu, Yanyun Zhang and Fumin Lei (2015).

Per Alström

Pam Rasmussen

Background:

Alström P., Fregin S., Norman J.A., Ericson P.G.P., Christidis L. & Olsson U. (2011).

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)