Parental care refers to the protection, care and feeding of eggs or offspring by parents. It has evolved independently multiple times in animals, e.g., mammals, birds, dinosaurs, arthropods, and especially various lineages of social insects.

Brood care is a form of uniparental care where parents carry eggs or juveniles after oviposition and provide protection, enhancing offspring fitness and survival. However, very few fossil insects directly document such ephemeral behavior. Among Mesozoic insects, the only two direct fossil cases of brooding ethology are from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota and mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber.

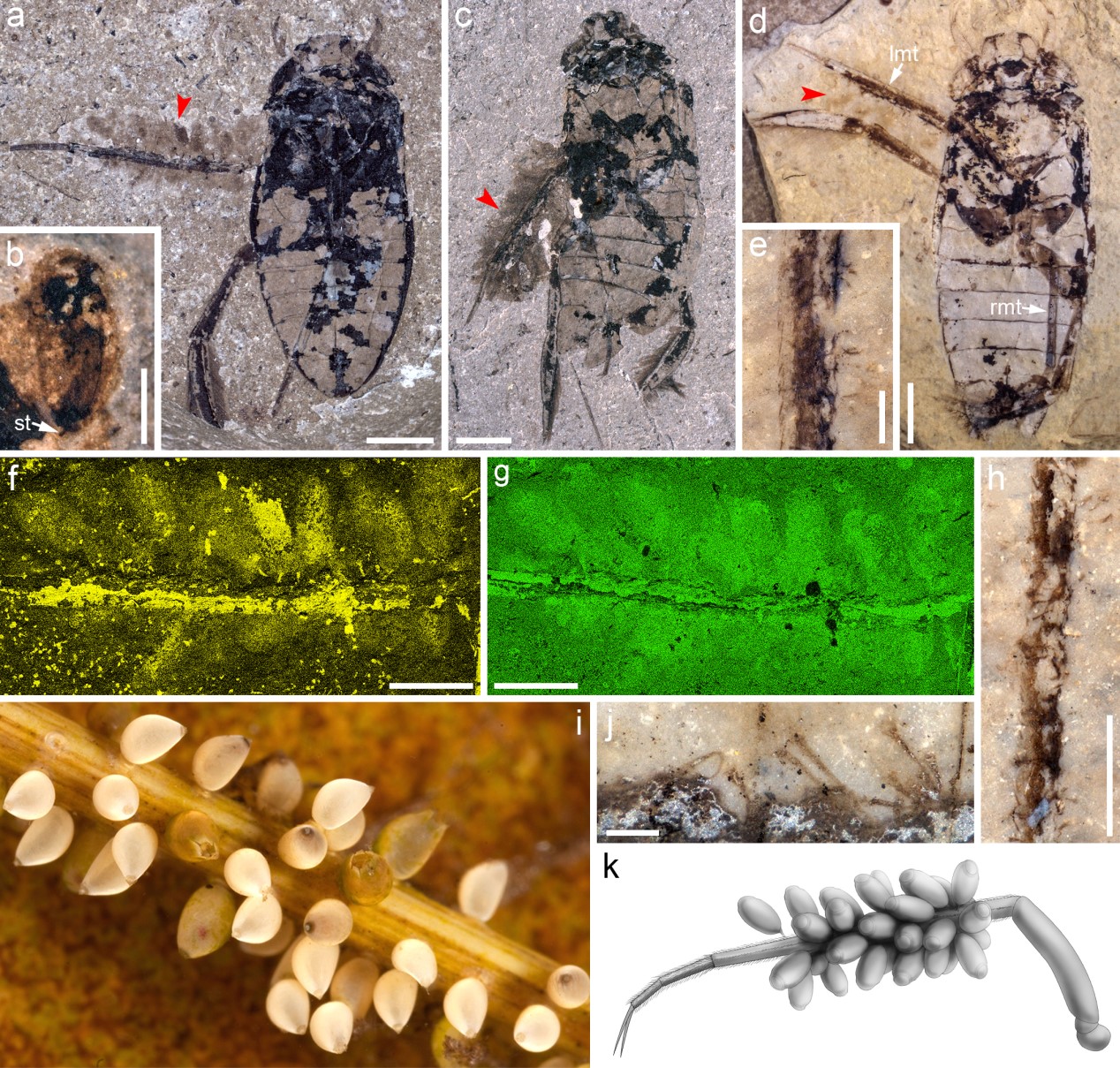

Recently, a research group led by Prof. HUANG Diying from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS) systematically studied the water boatman Karataviella popovi, a representative insect from the Middle-Late Jurassic Daohugou Biota of northeastern China. Of the 157 examined K. popovi fossils, 30 adult females were preserved with a cluster of eggs anchored on their left mesotibia.

This discovery represents the earliest direct evidence of brood care among insects, indicating that relevant adaptations associated with maternal investment in insects can be traced back to at least the Middle Jurassic, pushing back by approximately 40 million years evidence of such behavior.

The results were published online in Proceedings of the Royal Society B on July 13.

The true water bug superfamily Corixoidea, commonly known as the water boatman, is a common aquatic Hemipteran insect and occurs in various freshwater ecosystems worldwide. Extant water boatmen commonly deposit eggs on various subaquatic substances such as leaves or stems of aquatic vegetation, stones, and even on snail shells, carapaces of terrapins, and the exoskeletons of crayfish.

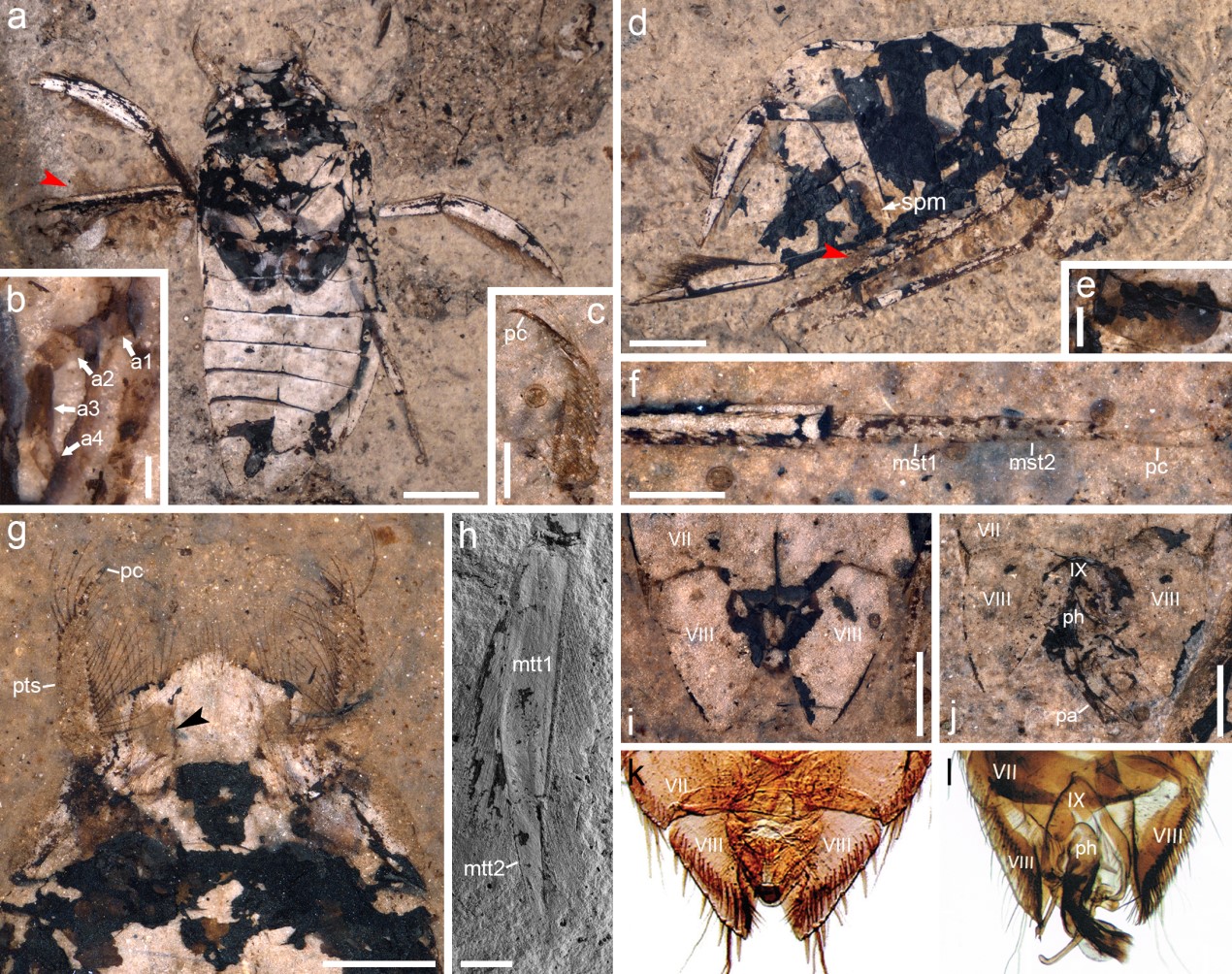

The Jurassic water boatman K. popovi from the Daohugou Biota has a relatively large body, with body length ranging from 11-15 mm.

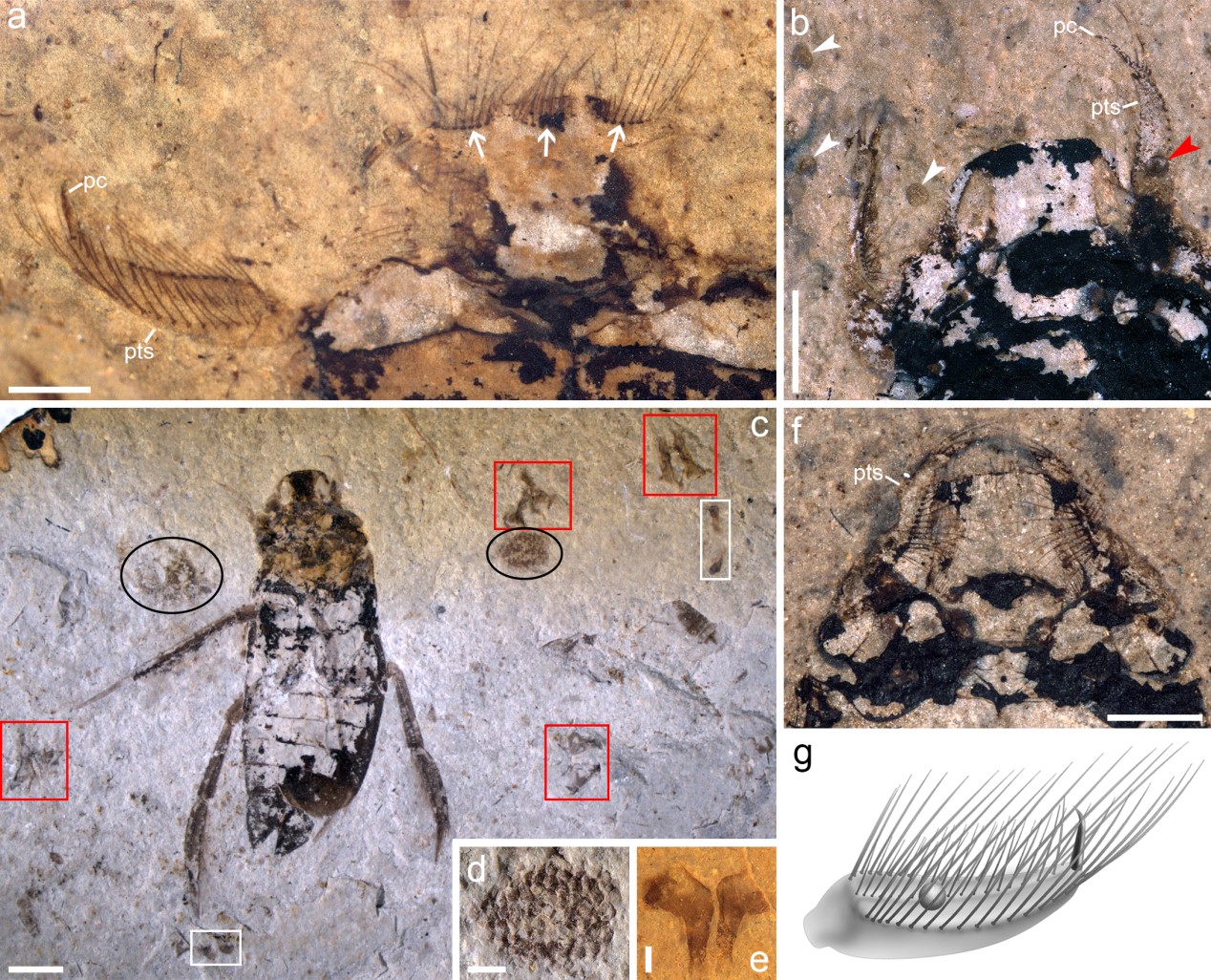

The specialized protarsi of K. popovi, combined with the five patches of setae on the head that form a trawl-like feeding apparatus, reflect highly specialized predatory behavior. Anostracans and the water boatman K. popovi, both found in the same layer of the Daohugou beds, represent precursors and dominators, respectively.

After the analysis of more than 700 anostracan eggs, the researchers hypothesized that the abundant seasonally produced anostracan eggs in the Daohugou Biota probably were the food source for K. popovi.

The egg clusters of K. popovi are compact and arranged in approximately five to six staggered rows, attached to and throughout the left mesotibia of adult females by short egg stalks. As inferred from the arrangement of the eggs, each row seems to have six to seven eggs. The diameters of eggs (without stalks) range from 1.14 to 1.20 mm.

"Due to the potential high predation risk caused by abundant salamanders in the Daohugou Biota and seasonal food resources, K. popovi may have been exposed to fierce ecological pressure in the Daohugou Biota," said Prof. HUANG.

The brooding behavior developed in K. popovi probably reflected adaptations to habitat or an evolutionary response to changes in the ancient lake ecosystem. The brooding behavior of K. popovi most likely provided effective protection for eggs by largely avoiding the risks of predation, desiccation and hypoxia. Such behavior had important effects on its evolution, development and reproductive success.

To our knowledge, carrying a cluster of eggs on a leg is a unique strategy among insects. However, it is not unusual in aquatic arthropods, where such carrying behaviour can be traced back to the early Cambrian Chengjiang Biota.

This discovery highlights the existence of diverse brooding strategies in Mesozoic insects, thus helping scientists understand the evolution and adaptive significance of brood care in insects.

Fig. 1. Morphological characterstics of K. popovi. (Image by NIGPAS)

Fig. 2. Brooding in K. popovi. (Image by NIGPAS)

Fig. 3. Specialized filter-capture apparatus in K. popovi. (Image by NIGPAS)

Fig. 4. Ecological reconstruction of K. popovi. (Image by NIGPAS)

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)