Artist's impression of Tsidiiyazhi abini. (Image: Sean Murtha)

The fossilised remains of a tiny bird that lived 62 million years ago suggests that birds burst out of the evolutionary gates once their dinosaur cousins were gone, rapidly diversifying into most of the lineages we see today.

Within four million years of the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event (K-Pg) — a mere blink of the eye in evolutionary terms — as many as 10 major bird lineages were already in place, according to new research published yesterday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. With the dinosaurs gone, and with habitats re-emerging, many of these pioneering species would diversify even further, eventually evolving into the 10,000 species of birds around today.

Birds evolved from dinosaurs, but dinosaurs didn't just suddenly become birds during the K-Pg extinction event. The relatives of modern birds first emerged around 125 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous. That's about 60 million years before that dreaded asteroid struck the Yucatan Peninsula, wiping out an estimated 75 per cent of all species on Earth — and virtually every creature larger than 25kg. The K-Pg event may not have created birds, but it did produce a filter through which only a select group of bird species were able to squeeze through. A similar process happened to mammals, and as a recent study pointed out, amphibians.

As the old saying goes, the meek shall inherit the Earth, and this is what scientists assumed happened for birds at the K-Pg boundary. Unfortunately, these feathered creatures, with their brittle and easily breakable bones, don't fossilise well, and there's a frustrating fossil gap around this time. That's why the discovery of a 62-million-year-old bird in the Nacimiento Formation in the San Juan Basin is so important. Fossil remains of the bird are re-affirming what palaeontologists have suspected, but haven't been able to prove — that little birds dusted themselves off after the asteroid strike, and began a path towards global dominance in the absence of troublesome dinosaurs and other competitors.

Artist's impression of Tsidiiyzhi abini. (Image: Sean Murtha)

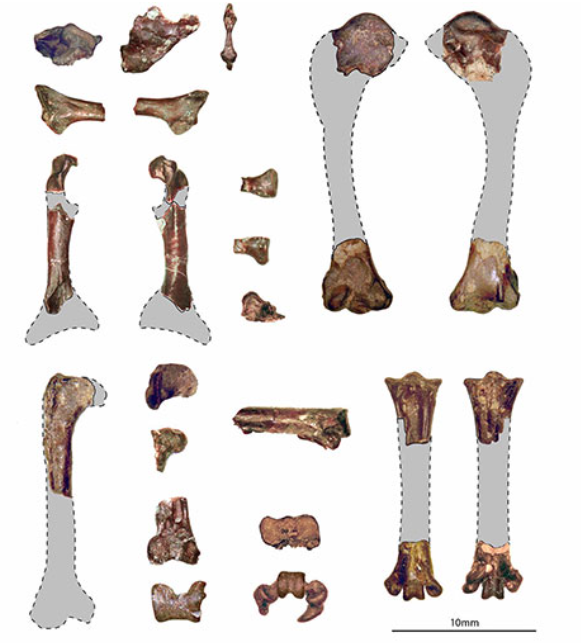

This sparrow-sized bird, dubbed Tsidiiyazhi abini (Navajo for "little morning bird"), lived in trees and liked to munch on fruits and seeds from flowering plants. It featured a unique fourth toe that helped it grasp and climb branches. It could even perform a complete about-face similar to modern owls. These physical characteristics, which were gleaned by researchers from the Bruce Museum, New Mexico Museum of Natural History, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, firmly place T. abini within an order of birds known as Coliiformes, or mousebirds.

Fossil bones of Tsidiiyazhi abini. (Image: D T. Ksepka et al., 2017)

That's significant, because the presence of this order at such an early date forces scientists to push nine related lineages, or clades, further back in time to the Early Paleocene. This suggests that the ancestors of virtually all birds seen today — from hummingbirds and woodpeckers through to vultures and ostriches — had emerged within four million years of the asteroid strike.

"The fossil provides evidence that many groups of birds arose just a few million years after the mass extinction and had already begun evolving specialisations of the foot for different ecological roles," noted the authors in their study.

As this study shows, it's not just the meek who inherit the Earth — it's also the quickest. Birds, with their ability to fly, were certainly in a good position to claim the many emerging ecosystems as their own. (GIZMODO)

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)