Researchers in China have discovered a fossilised skull of a sabertooth cat, which they say is the biggest ever found.

The skull measures around 40 centimetres long, which translates to an enormous estimated body mass of over 892 pounds, and body length of 3.1 metres - equivalent to a male polar bear.

While the cat has the distinctive fangs, its gape was much smaller than other cats, which suggests it targeted smaller prey.

Researchers in China have discovered a fossilised skull of a sabertooth cat, which they say is the biggest ever found. The skull measures around 40 centimetres long, which translates to an enormous estimated body mass of over 892 pounds.

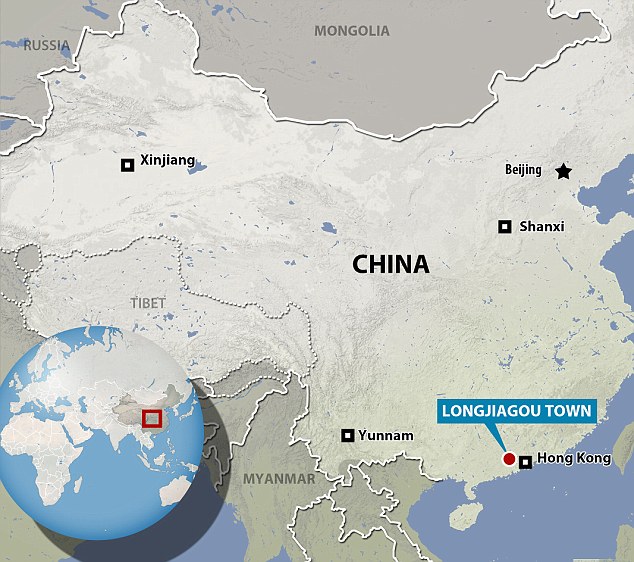

The researchers, from the Chinese Academy of Science, found the fossil, which is roughly 8.3 million years old, in China's Longjiagou Basin.

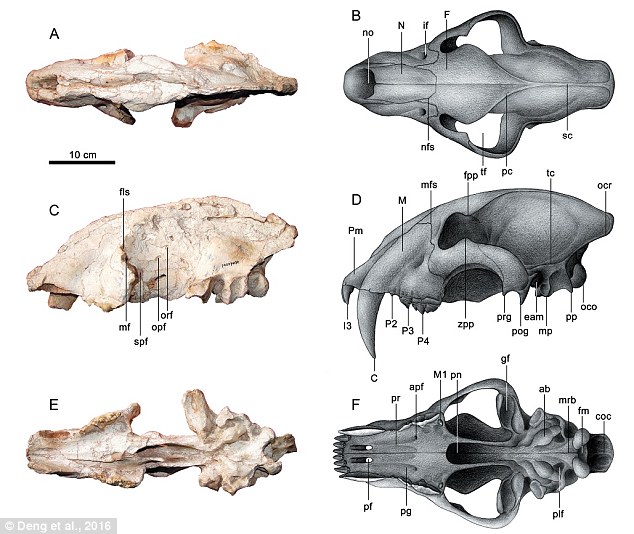

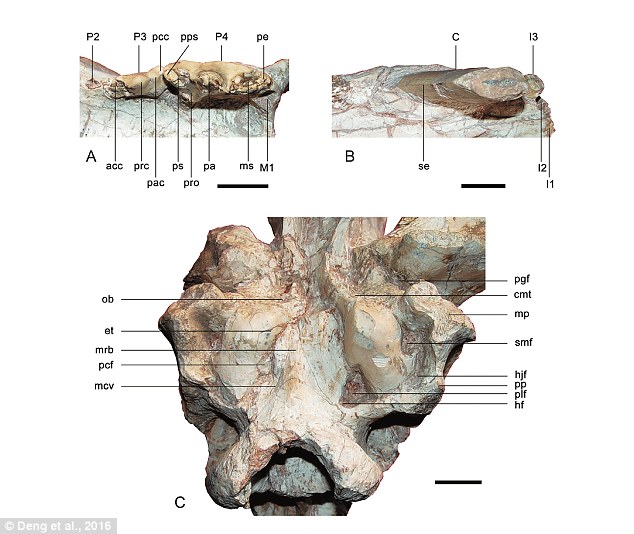

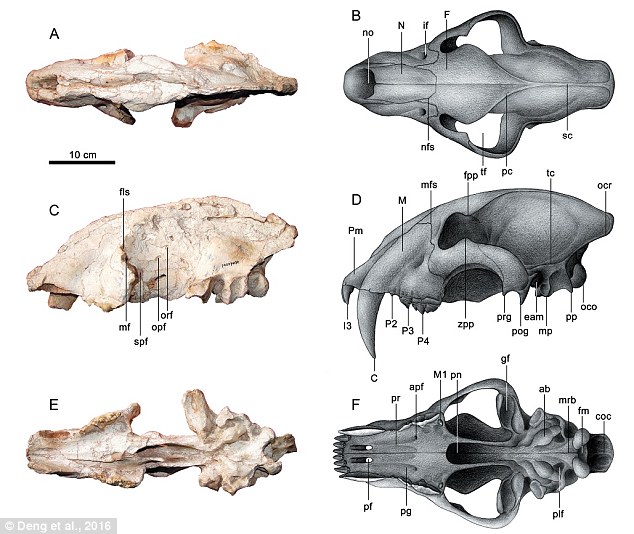

Although it was slightly crushed, the researchers were able to identify the cat as a Machairodus horribilis – a menacingly large cat from the Late Miocene of northwestern China. The huge skull is longer than any other known skull of both contemporary sabercats, but also those of the Ice Age.

Tao Deng, who led the study, told MailOnline: 'This sabertooth cat has a shoulder height of 1.3 m and a body length of 2.4 m (3.1 m with its tail).'

For comparison, this is roughly the same size as a male polar bear.

In their paper, published in Vertebrata Palasiatica, the researchers wrote: 'It shares some characteristics with derived sabertooth cats, but also is similar to extant pantherines in some cranial characters.' Like other sabertooth cats, the Machairodus horribilis had long serrated fangs, but its gape was much smaller.

Overall the researchers believe that the findings could offer an additional mechanism for evolution, leading to functional diversity in sabertooth cats (artist's impression)

Although the skull was slightly crushed, the researchers were able to identify the cat as a Machairodus horribilis – a menacingly large cat from the Late Miocene of northwestern China

Like other sabertooth cats, the Machairodus horribilis had long serrated fangs, but its gape was much smaller. The cat would only be open its mouth about 70 degrees, rather than the huge 120 degrees that the Smilodon, an Ice Age sabertooth cat, could achieve

The cat would only be open its mouth about 70 degrees – comparable to what modern lions can do.

This is small compared to the 120 degrees that the Smilodon, an Ice Age sabertooth cat, could achieve.

The researchers suggest that this shows that the Machairodus horribilis may have targeted smaller prey than later cats went for.

The researchers write: 'Its anatomical features provide new evidence for the diversity of killing bites even within in the largest saber-toothed carnivorans.'

Overall the researchers believe that the findings could offer an additional mechanism for evolution, leading to functional diversity in sabertooth cats.

The fossilised skull was found in Longjiagou Town, in China's Longjiagou Basin

SABRE-TOOTH TIGERS DIDN'T GET THEIR FANGS UNTIL THEY WERE THREE

The sabre-tooth tiger may have been capable of slaying mammoths and rhinos, but it only had relatively small teeth until the age of three.

Research suggests that the animal's impressively long, dagger-shaped teeth developed later in life than modern cats do.

But once they emerged, they grew twice as quickly as the lion's, for example.

A partially fossilized jaw from an adult Smilodon fatalis saber-toothed cat showing a fully erupted canine - which didn't appear until later in life.

The sabre-tooth tiger, now more accurately known as the sabre-toothed cat, Smilodon fatalis, lived in North and South America until it became extinct 10,000 years ago.

The big cats are famous for their protruding canines, which could grow up to seven inches (18 cm) long.

Although well-preserved fossils are available to researchers, very little is known about the ages at which the animals reached key developmental stages and grew teeth, for example.

Researchers from Clemson University in South Carolina examined specimens recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles

They used data from stable oxygen isotope analyses with X-rays and information from previous studies to calculate when the prehistoric cats' permanent upper canines came through, as well as other growth events.

They believe that the cats got most of their teeth by 14 to 22 months, with the exception of their famous 'fangs'.

The experts say the long teeth didn't develop until the cats were around three years' old, which is delayed in comparison to similar-sized living members of the cat family. (Daily Mail)