The pterosaur record is generally poor, and pterosaur eggs are even rarer. Only a handful of isolated occurrences of eggs and embryos have been reported so far. Three-dimensionally preserved eggs include one from Argentina and five reported from the Turpan-Hami Basin, Xinjiang, northwestern China in 2014. Our understanding of several biological questions, including their ontogenetic development and reproductive strategy for pterosaurs is very limited.

After many extensive fieldwork in the past years, Dr. WANG Xiaolin, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), and his team reported on hundreds of three-dimensional (3D) pterosaur eggs of the species Hamipterus tianshanensis from a Lower Cretaceous site in the Turpan-Hami Basin, 16 of which contain embryonic remains, allowing for an unexpected look at the embryology and reproductive strategy of these flying reptiles. Their study was published online 30 November in Science.

"The specimens can be attributed to Hamipterus tianshanensis, the sole species in this bonebed. The most important section is a sandstone block (3.28 m2) that yielded 215 eggs, but up to 300 may be present, because several more appear to be buried under the exposed ones", said Dr. WANG Xiaolin, lead author of the study and project designer of the IVPP.

The eggs are in an accumulation without a preferential orientation, clearly showing transport. Their external surface shows cracking and crazing, and all are deformed to a certain extent, which indicate their pliable nature. Although most eggs are complete, small fissures resulting from decomposition and compression during burial must have occurred because all eggs are filled with sandstone, which ultimately accounts for their three-dimensionality.

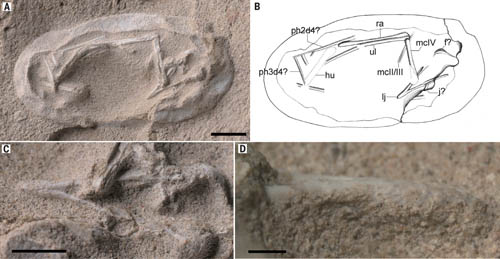

Internal content could be observed in 42 eggs, either through computed tomography (CT) scanning or micropreparation. From these, 16 had embryonic remains (38% of the sample). Bones are distributed along the egg, and mostly disarticulated and displaced from their natural position.

No embryo is complete, with osteological material varying from one to several bones. This can be explained by several factors, including the presence of embryos in distinct embryological stages, differential preservation of bones, and loss of elements during transport and burial, with part of the egg content expelled. The skull roof was not well ossified before the animal hatched, and no teeth were found in any of the embryos.

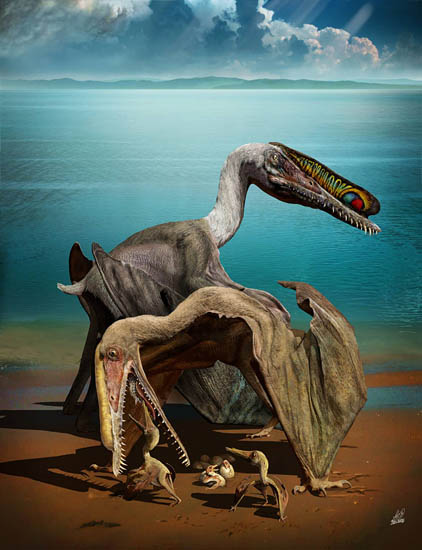

"Although the current available material cannot provide a complete view of the ontogenetic development of Hamipterus, and despite some uncertainty in regarding these embryos as representing late embryonic stages, some general observations can be made that considerably expand our knowledge about the embryology and ontogeny of pterosaurs", said co-corresponding author Dr. Alexander Kellner, Department of Geology and Paleontology, Museu Nacional–Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, "computed tomography scanning, osteohistology, and micropreparation reveal that some bones lack extensive ossification in potentially late-term embryos, hatchlings were likely to move around but were not able to fly, leading to the hypothesis that Hamipterus might have been less precocious than previously assumed for flying reptiles in general and probably needed some parental care."

Most eggs were collected from white to gray, middle- to fine-grained sandstones that were deposited in a fluvio-lacustrine environment where mudstone pellets and localized lenses of mudstone are present, suggesting that events of high energy such as storms have passed over a nesting site, which might have caused the eggs to be moved inside the lake where they floated for a short period of time, becoming concentrated and eventually buried along with disarticulated skeletons.

"Our findings further demonstrate the exceptional conditions necessary for the preservation of such fragile material and can explain the notable paucity of pterosaur eggs and embryos in the paleontological record compared to other reptiles, because the preservation potential of soft-shelled specimens is regarded as very poor”, said co-author Dr. JIANG Shunxing of the IVPP.

"Furthermore, this occurrence implies colonial breeding for Hamipterus tianshanensis, as demonstrated by the osteohistological identification of individuals in different growth stages, a hypothesis previously speculated for pterosaurs on the basis of very limited evidence. Our discovery may indicate that gregarious behavior and potential nesting site fidelity might have been widespread among derived pterosaurs," said Dr. JIANG Shunxing.

This study was mainly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of CAS, the Hundred Talents Project of CAS, the Excavation Funding and Emphatic Deployed Project of IVPP, CAS.

Fig. 1 More than 200 eggs of Hamipterus tianshanensis preserved in sandstones (IVPP V 18941 to 18943), scale bar 200 mm (Image by WANG Xiaolin)

Fig. 2 Eggs preserved with pterosaur bones (IVPP V 18942). (A) Close-up of egg concentration, scale bar 100 mm; (B to F) selected eggs, Scale bar 20 mm. (Image by WANG Xiaolin)

Fig. 3 Embryo 12, the most complete one, containing a partial wing and cranial bones, including a complete lower jaw. Photo and line drawing showing the lower jaw exposed in ventral view (A, B), scale bar 10 mm; (C) Close-up of the lower jaw, scale bar 5 mm; (D) Close-up of the anterior portion of the lower jaw in left view, scale bar 1 mm (Image by WANG Xiaolin)

Fig. 4 Life reconstruction of Hamipterus tianshanensis (Image by ZHAO Chuang)

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)