Researchers have used centuries-old Chinese cave inscriptions and stalagmite analyses to predict how much rain a region will get in the future.

Near the Hanjiang River in central China, amid the lush, pine-covered Qinling Mountains that once were dotted with Daoist shrines and where giant pandas now roam, is the Dayu Cave. Its entrance is small, only a few meters high and wide. Inside, a matrix of passageways and chambers branch off from a main tunnel that runs a little more than a mile. The air is humid, and ancient stalagmites swell upward from the cave floor.

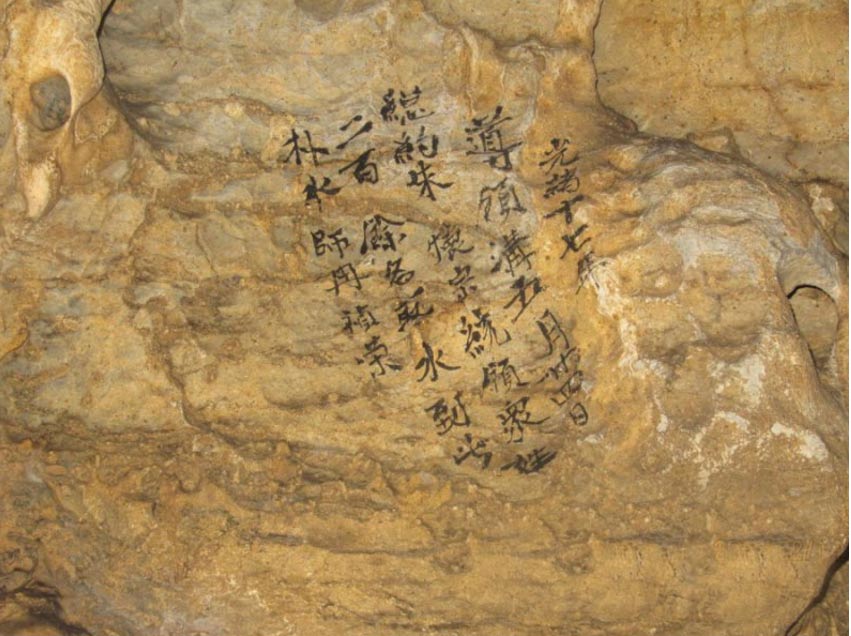

Climatologist Liangcheng Tan first visited the cave a decade ago and noticed ink inscriptions written on its walls and formations. He figured they were poems and didn’t think much of them, as it is common to find poems that scholars wrote long ago in Chinese caves. But when Tan visited again in 2009, he studied the inscriptions more thoroughly and realized they were drought records dating back half a millennium.

"Previous people didn’t carefully examine the inscriptions,” says Tan, an associate professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. But he knew they could provide an unprecedented opportunity to study climate change in the region, matching chemical analyses of the stalagmites to the drought record inscriptions.

Tan says the study marks the first time researchers have been able to do an on-site comparison of historical and geological records from the same cave. “The inscriptions were a crucial way for us to confirm the link between climate and the geochemical record in the cave, and the effect that drought has on local society,” he says, echoing earlier statements he’s made.

"This is quite unusual. It’s the first time I’ve come across something like this,” says Sebastian Breitenbach, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Cambridge who co-authored the study. Most older cave inscriptions he’s come across in Siberia and elsewhere have been the equivalent of the modern-day I Was Here tag, he says. “These inscriptions are special because it gives a date, so we know by the day when they were there...what they did there, why they went to the cave.”

Inscriptions from 1891 say, “On May 24th, 17th year of the Emporer Guangxu period, Qing Dynasty, the local mayor, Huaizong Zhu, led more than 200 people into the cave to retrieve water. A fortuneteller named Zhenrong Ran prayed for rain during a ceremony.”

The researchers published their findings last week in Scientific Reports. They took stalagmite samples from the cave back to a lab in China, where they sliced them open and drilled deep into them. Chemical dating and isotope analyses provided information about rainfall patterns over centuries, which the researchers checked against the inscriptions of seven drought events from 1528 to 1894. The researchers then created a model that could predict future rainfall in the region. The model suggests a drought will occur in the late 2030s.

The cave apparently held important meaning for locals in times of little rain. The inscriptions describe how people and government officials visited the cave to collect water and pray for rain. Historians have linked environmental change to the fall of several dynasties, and the 1528 drought led to starvation and cannibalism. “Mountains are crying due to drought,” the inscriptions say.

Though the Dayu Cave today is a tourist attraction, locals have kept it in relatively good condition. “Anything you put on the wall will stay on the wall for a very long time,” Breitenbach says. “Caves are very protected from the outside environment. That’s what makes them special for climate archives.” The oldest known cave paintings, in Spain and Indonesia, are believed to be from around 40,000 years ago.

Tan says, however, “We do see some disturbances of the ancient inscriptions made by modern visitors.”

Even without accompanying inscriptions, stalagmites contain vast information. “It is like a library,” Breitenbach says of caves. “The stalagmites are like the books and in the books you have letters and pages of letters.” They develop a new layer every year, similar to tree rings.

Echoing previous statements, Tan says he hopes the findings will emphasize “the importance of implementing strategies to deal with a world where droughts are more common.” (Newsweek)

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)