|

|

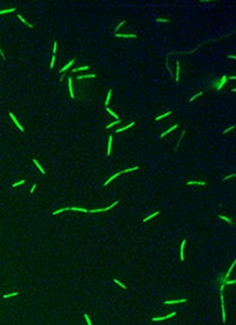

Biologist Cui Qiu carries out tests on the germ clostridium, in a bid to produce new biofuels. Photo: Dr Cui Qiu |

In science fiction movies, scientists manipulate genes of tiny organisms to create powerful new life forms. How do you feel when working in the laboratory?

Dealing with bacteria is not always as easy as it seems in the cinema. Indeed, for a few bacteria such as E coli, we now have a lot of knowledge and tools. E coli, for instance, has been studied by many scientists for a very long time. We know the function and role of Clostridium. Photo: Dr Cui Qiu

almost every one of its genes, and many tools have been developed for genetic engineering. With these bacteria, scientists can indeed do almost everything at will. But the ones we are familiar with account for only a tiny, tiny, tiny fraction of all microorganisms. Most germs live and thrive in ways far beyond our grasp. Clostridium, for instance, was extremely difficult to deal with. Before our research, scientists knew very little about the function of its genes and there were no effective tools to use. The knowledge we had of E coli and the methods we used with it could not be applied to clostridium because they are as different as crocodiles and pigs. A chemical injection that enlivens E coli might very well kill clostridium. With every new bacterium, researchers have to start from scratch. A sense of defeat is more common than a sense of power.

What are the technological challenges that limit the production and use of biofuel generated by bacteria? How long do I need to wait before my car can be filled with germ-made fuel?

I don't think the technology is a problem. Scientists have turned numerous microorganisms into impressive producers of biofuel that are highly efficient from the perspective of energy conversion. The biggest issue today is cost. The price for a tonne of ethanol, for instance, is less than 5,000 yuan (HK$6,332). If ethanol is produced from sugar using traditional methods, the sugar alone would cost more than 6,000 yuan. Our new method with clostridium could reduce the sugar requirement and bring the total cost close to ethanol's market price. But then there is no profit. A biofuel must be able to compete with fossil fuels, such as petrol. But there is hope. Fossil fuel resources are declining and leading to more and more complaints about pollution and the price rises are basically irreversible. The higher the cost of fossil fuel, the more demand there is for various biofuels.

What about clostridium? Why did you choose it?

The clostridium name is derived from the Greek word for "spindle" because it has cells similar in shape to a rod. Scientists have known about it for a long time, as it occurs in rotting wood. Scientists found it had a particular taste for wooden fibre. But the natural species was not suitable for industrial-level production of biofuel because it died easily in a heated environment, consumed certain types of wooden fibre and produced ethanol slowly. But I was quite intrigued by the bacterium and gave it a chance.

Are you taking over the role of nature?

No, I am not better than nature. Nobody can be. However sophisticated human technology is, it cannot compete with the wisdom and power of natural selection that might have started soon after the birth of the earth. I have been deeply impressed by the work of nature and I look to nature to guide which germs I should choose as candidates. But from the standpoint of humans, natural selection has one problem: It does not always work to our benefit. Most of the time, if not always, it works only to the benefit of a particular species. Clostridium, for instance, does not want to release too much ethanol. Its main concern is to survive and live well. It cares nothing about our energy shortage or air pollution. In order to make it produce a large amount of ethanol in an environment it might not like, we had to use various tools to manipulate its genes. We can knock out some unwanted genes with the use of electricity or introduce some favourable genes with a chemical agent.

You deal with germs every day. Do you worry about safety?

The bacteria we deal with are harmful to humans but also very timid. They don't carry any lethal genes. As scientists, we know what we are dealing with. There are some germs you don't touch because they can cause illness. But people don't need a security pass or wear protective suits to get inside our laboratory. I am not worried about safety issues.

But people do worry that scientists might create highly lethal pathogens that could cause havoc if they escape from the laboratory. As a bacteriologist, are you concerned about that?

There is no denying that the development of biological weapons presents a risk. I urge scientists who participate in such research to rein in their curiosity and maintain high moral and ethical standards. I don't think any well-trained scientist would attempt anything crazy, but we all need to honour and comply with safety regulations. China is doing well on that front, in my opinion. Chinese scientists are now exploring many unknown areas shoulder to shoulder with overseas competitors. We have received increasing funding from the government, but we also face greater pressure because China is now troubled by many issues, such as energy shortages and air pollution. We must help. (South China Morning Post)

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)