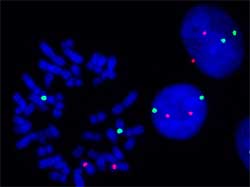

The number of chromosomes can be detected in human metaphase (Left) and interphase (Right) cells by fluorescence in situ hybridization using chromosome-specific probes. Red and green dots represent hybridization signals for human chromosome 8 and 12, respectively.

Cancer is a primary threat to human health as it kills millions of people each year. Scientists have shown that 75% of human cancers have an abnormal number of chromosomes in cells, and the proportion of the cells with an abnormal chromosome number is tightly and positively related to malignance progression and metastasis of cancers. But the pathological mechanism behind the anomaly still remains unknown.

In cooperation with Dr. Randall King from the Harvard University, Prof. SHI Qinghua, formerly a research fellow at the Harvard University and now working at the CAS affiliated University of Science and Technology of China (USTC), offers a possible explanation to the puzzle. Their work was reported in the Oct.13 issue of the journal Nature.

By using live cell imaging and fluorescence in situ hybridization, a molecular cell biology technique, the researchers tracked the process and result of a cell division and detected chromosome composition of the cells. In this way, they revealed that chromosome nondisjunction, a kind of chromosome mis-segregation, leads to the failure of completion of cytokinesis, resulting in cells with two nuclei, called binucleated cells. Usually, the binucleated cells arrest in interphase of cell cycle. However, if they enter mitosis, cells with inaccurate chromosome numbers may be produced, eventually leading to the emergence of cancer.

Together with an independent research, also published in the same issue of Nature, the work lends experimental support to the ideas that errors in cell division contribute to the development of cancer, which was first proposed by German biologist Theodor Boveri in 1915.

According to Prof. Shi, who is also a principal investigator at the Hefei National Laboratory for Physical Science at Microscale, USTC, the result was attained in cultured human cells. So far, it is unclear whether a similar mechanism exists in human bodies or in animal cells in in vivo. How does a cell detect error(s) in chromosome distribution during cell division? How is cell division stopped after the error has been identified? What factors are involved in the determination of whether a cell with two nuclei can undergo cell division or not and, how? All of these questions are needed to be further explored. His lab is now focused on these questions, with the hope of providing theoretical bases for eliminating or relieving the untold human sufferings caused by the cancer.

86-10-68597521 (day)

86-10-68597289 (night)

52 Sanlihe Rd., Xicheng District,

Beijing, China (100864)