Offering lectures both on science frontier and practical skills, a training course on food biotechnology specially tailored for developing countries showed how biotechnology can upgrade ancient approaches to food production, like fermentation.

"A small sachet of the seed starter can produce over one hundred of meals,” Dr. Wilbert Sybesma waved a small package when introducing “Yoba”, a yoghurt-like beverage based on local-sourced probiotic bacteria strains to the participants at a food biotechnology training course occurring in Beijing: “It is very very affordable,” he asserted. When asked about the shelf life of the sachet, his answer stirred a wave of excitement: “At least three years under ambient environment.”

Dr. Sybesma was teaching at the 2015 Food Biotechnology Training Course for Developing Countries occurring from November 26 to December 2, 2015 in Beijing, organized by the CAS-TWAS Centre of Excellence for Biotechnology (CoEBio, http://www.cas-twas-coebio. org/), which is based in the CAS Institute of Microbiology (IMCAS, http://www.im.cas.cn). Through dissemination of biotechnology, the organizers hoped to help promote science excellence in developing countries, targeting the needs of the local social and economic developments. The training course covered fundamentals of fermentation, including the dynamics and products of the metabolic process in microorganisms, the potential of fermentation to improve food quality and increase nutritional value, modern techniques of strain selection and optimization, and practical skills needed in lab experiments, grant application, academic publication and team building. On top of these, a practical workshop embedded in the training offered an exciting opportunity for the participants to turn their dreams true: they were encouraged to propose their ideas to develop new fermented foods for their local people, aiming at solving some local issues. The outstanding proposals would win financial and technical aids from the organizers.

Dr. Wilbert Sybesma tells the story of “Yoba”. (Photo by SONG J.)

Dr. Sybesma, currently working for Nestlé Research Center, co-founded the Yoba for Life Foundation, a non- profit organization active in East Africa that aims to improve health and wealth in developing countries through the development, production and distribution of Yoba. An important idea of this project involves establishing indigenous ability to produce this healthy, affordable beverage. For this sake Dr. Sybesma not only shared his team’s experience of Yoba, but also the science involved in developing the starter yeasts, particularly modern biotechnology for strain selection and optimization.

Trainees in class. (Photo by SONG J.)

Magic Powder

"The secret of its long shelf life is,” answered Dr. Sybesma to the inquiry of a trainee: “We made it very dry — the drier the better, and stored it together with some dry starch, which supplies the strains with maintenance energy to survive at low metabolic rates.”

This handy sachet starter consists of optimized strain combinations of probiotic bacteria identified and selected from the local environment of Uganda. Using local species and strains makes it easier for the microbial community to survive; also it promises better robustness in presence of adversity. “Another reason is the costs,” Dr. Sybesma added: “Otherwise the end products could be too expensive for the local people, which would not be what we expected.”

This magic powder interested the audience immediately. “Maybe we can find some local probiotic strains and make our own brand of ‘Yoba’,” said Furqana Khalid Chaghtai, a trainee from University of Karachi, Pakistan. “It’s better than importing the microbes from Uganda, at least for a better survival of the probiotics,” she laughed. According to Afolake Atinuke Olanbiwoninu, trainee from University of Ibadan, Nigeria, they have in their country a fermented beverage similar to yoghurt. “Therefore Yoba is not exotic for us,” she commented, agreeing it is easy to transplant the idea to her homeland, though geographically Nigeria is not so close to Uganda, where the “Yoba for Life” concept has thrived for years.

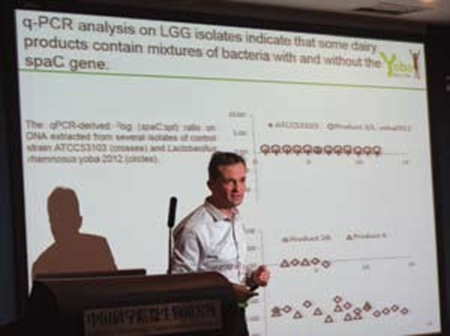

More important secrets of the starter for Yoba, however, lie in the science profoundly seated in the construction of the microbial community, which has demonstrated excellent quality, stability and robustness. To deliver the involved knowledge, Dr. Sybesma prepared three lectures, with the first focusing on the probiotic bacteria themselves, including the concept of such special species, the characters distinguishing themselves from other bacteria, health benefits of them for humans, how they survive the digestion process and the acid environment of human intestinal tracts to work alive at the depth of the guts, and methods of identifying the strains from their environment.

Valued Seeds

"What should you rescue if you could choose only one thing from your bakery when it caught fire? The dear piece of old sourdough.” — An experienced baker

The value of a good leavening agent for a bakery could never be over-stated, but only very few people know the secret of the microbiota involved.

The microbial community in a starter culture for fermentation could be extremely complicated, as the result from a long evolution process of an ecosystem comprised of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria (LAB), and probably molds

— which could be annals of wars among species and strains. This means the compositions, and the subtle equilibrium or the robust symbiosis among different actors in the community could be impossible to replicate. The same uniqueness constitutes the value of the seed starter of Yoba. How did they make it? Dr. Sybesma unraveled the secrets in the yeasts in his second lecture.

Particularly, Dr. Sybesma introduced techniques for strain construction and selection, illustrating how to meet different goals with aid from modern biotechnology, for example how to make the colons more acid tolerant (which is important for their survival in human guts), more stable at high temperatures, and more productive; and how to improve the nutrients in the end product through manipulating compositions of strains in the starter. For this sake Dr. Sybesma introduced multiple techniques, both genome modification (GM) and non-GM techniques involved in screening and selection of desired strains, including random mutagenesis (spontaneous or induced) and site directed mutagenesis, dominant selection schemes, and single-strained DNA recombineering. This arrangement provided alternative options for consumers who are concerned about genetically modified foods.

In his third lecture Dr. Sybesma introduced the concept of and the latest research on bacteriophages, which are seen as a possible therapy against multi-drug-resistant strains of many bacteria, as a potential way to combat bacterial infections in developing countries.

Dr. Herwig Bachmann from NIZO Food Research, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam of the Netherlands also dealt with the choice of organisms and their improvement/selection for desired metabolic activities in food fermentation. He touched on more technical details, including how to characterize different organisms based on sequence information and high throughput phenotyping. With attention cast to the biodiversity of the ecosystem and interactions between strains, his introduction of quantitative methods like metabolic modeling and cases of growth strategies made his illustration of experimental evolution of industrially relevant traits more inspiring.

A trainee-lecturer discussion. (Photo by SONG J.)

Dr. Wilbert Sybesma explains to the audience how to isolate probiotic bacteria from the environment. (Photo by SONG J.)